It’s past midnight, and I’m sitting at the airport in Istanbul.

The poet’s brother and his fiancée, Zehra, are on their way to pick us up for their engagement ceremony weekend.

As I have mentioned, I have not been very cool about this whole situation. Earlier today, in an attempt to make myself… more cool? Polished? Feel like I’m more in control even though I’m not?… I got a mani-pedi at the local salon in Grape Village. The woman who gave it to me was horrified at my fingernails (“too short!”) and my hair (“more highlights would look better”) and probably other things she didn’t get around to mentioning. I don’t understand why people in the beauty industry do this—shouldn’t they want us to feel more beautiful when they leave their place of business?

I raced home from the salon on my bike, scuffing my newly painted toenails, so we could catch a small bus and then a bigger bus and then a plane to Istanbul—all the while hauling Django, a suitcase and two carry-ons. The poet handled all of this the way he handles almost everything: with ease, kindness, bad jokes, and snacks. I grumbled, and I sweated.

Now, in the airport, I am still sweating. I am, in fact, having a hot flash. Django is barking like it’s his job. The poet and I are both starving as we’ve made a pact to stay off of gluten and sugar until the ceremony, and we’re sitting in front of a bakery with 12 kinds of chocolate pudding on display.

We walk up and down the airport hallway, trying to rationalize chocolate pudding as the only viable food option.

“Sugar doesn’t count when it’s consumed at an airport, right?” the poet asks.

I am too boiling and too grouchy to find this funny.

We find a sort of grocery shop, and settle down on a bench with a strange kind of picnic of rice cakes, ayran and dark chocolate. To our right is a family of four. The woman is covered, the man is in shorts. Of course this is a sight I’m used to seeing here, and I’ve always tried to be as open-minded as possible about it. After all, it is not about me.

But for obvious reasons, it’s been on my mind a lot lately. Right now, all I can see is that this woman must be sweating even more than I am, while she cares for two kids and her husband feels the cool breeze on half of his body.

The dark cloud over my head grows darker.

We lay out our food, and I knock over a can of Red Bull someone has left behind. It spills on my hands and pants, and I swear under my breath, trying to mop it up before Django gets to it, as Red Bull is exact opposite of what my dog needs in life. A fistful of wet wipes appear in front of me. It’s the woman with the head covering. Our eyes meet. She gives me a huge, knowing smile.

The dark cloud fades.

I smile back, gratefully. She coos over Django. Then they pack up their stuff up and walk away, and as the father scoops up the daughter, I see that she is severely disabled. I wonder what life is like for this family. What hardships have they gone through? Which ones are still to come?

Without warning, the dark cloud disappears completely.

We don’t get to bed until 3am that night, and by “bed”, I mean some blankets on top of some yoga mats on the floor, as the poet’s brother and Zehra have just moved into a new house. Floor-sleeping is not high on my list of ways of pretending to be cool, but I manage not to complain. The next morning, over breakfast, I meet two of Zehra’s friends Zehra, one of whom speaks great English and seems keen to practice it with me.

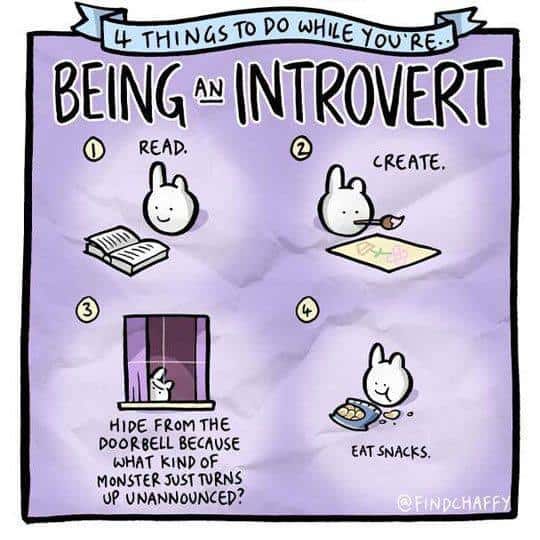

I crawl back up to our room to sit on the floor-bed and eke out some introverting before the festivities begin work. Half an hour later, the English-practising friend appears at the top of the stairs, plops herself down net to me and starts to chat. Then the poet’s mum appears to ask if we need anything ironed. Later, I’m in the shower and someone knocks on the bathroom door to see who’s in there.

They don’t do privacy in this place, do they, I text my friend Willow, who’s lived here for six years.

Nope, she texts back. You gotta fight for it.

But weirdly, today, I don’t want to fight for it. I am so used to a life where not texting before you call or not making an appointment via calendly is considered rude. I think of stories my parents tell about living in Beirut, where they spent entire Saturdays either visiting people’s houses unannounced, or having people visit theirs. I like that, here, people just assume you want to be in their company.

Obviously, I obsessed over what to wear today. I’ve never been to a Turkish engagement ceremony, and the poet’s only hint was to dress for it the way I’d dress for a wedding.

“What kind of wedding?” I demanded. “A Lebanese wedding?” (Where people dress for the red carpet at the Oscars.) “A Canadian wedding? A country chic wedding?” (“What’s that?”) “A Turkish village wedding?”

He shrugs. “Why does it matter?”

We’ve just moved to the sticks a week ago. We still don’t have a car, and are up to our eyeballs with non-functioning appliances and no internet, so a day in town for a shopping trip isn’t an option. Finally, on the advice of Willow—“Just wear what you have! If they don’t like you, too bad for them!”— (did I mention she’s from New York?), I put on a long, hippy-ish dress and sandals. I feel sheepish next to Zehra, who is even more stunning than usual in Mad Men-style white dress and updo with flawless makeup and, no word of a lie, glass slippers.

Then the other guests show up. Some are in formalwear. Most are in jeans.

The backyard has been decorated for the event. It has a bunch of small bar tables, and an arch. I stand on the balcony, gazing down at the scene.

My own wedding was almost exactly 13 years ago. A dear friend of mine built an arch for it, which we later moved to our garden. I remember how much hope I had that day, how many plans I had, how much detaile I poured into thinking about them.

I realize with shock how much I envy Zehra for having that hope.

To have a party to honour her engagement to the man she loves.

To have an arch.

This is how the engagement ceremony goes:

First, we eat a lot. (Surprise!)

Then, Zehra serves her betrothed a cup of coffee with salt in it. Him drinking it is a symbol of his commitment, and a reminder that marriage is not always sweet.

They put on two rings, which are tied together with a red string, which the poet’s father then cuts.

Everyone cheers.

Everyone drinks.

Everyone eats cake.

That’s it.

The photo-taking in front of the arch, though, goes on all night. The bride and groom alone, then posing with the parents, then without the parents, with the friends, with the cousins. Then with the poet and me and Django. Then, to my surprise, Zehra wants a photo with the poet’s mom, and me.

As we stand and smile, I feel Zehra’s arm reach behind her mother-in-law-to-be and squeeze mine.

My heart cracks open, and I squeeze hers back, blinking away tears.

“You are part of the family now,” the poet’s dad says, later that night.

I was part of another family once. It was wonderful and it was terrible.

I lost myself, because I didn’t know how to keep myself safe. I wrote about it to cope, which was maybe not so compassionate to the people I was writing about. Then I left, vowing to never lose myself like that again, and thus to never get involved like that with anyone again.

I don’t have that feeling now. This feels like a choice, not an expectation.

That night, after translating what his father said, the poet added, “You are part of the family, no matter what happens between you and I.”

This is, to me, is what being part of a family means.

At around 11 o’clock, everyone is sitting around inside, trading photos and eating silver-wrapped chocolates.

“They are going to the Dream Cafe,” the poet tells me. “Would you like to come?”

I change and we get into the car. Turns out “Dream Cafe” is a heaving nightclub on a dead end street, where a long-haired DJ pretends to play various instruments while spinning 90s music and Turkish dance tracks. A beer is pressed into my hand, and we all sing along and leap around like teenagers. The poet’s brother, surrounded by his buddies, is in heaven. Zehra relaxes, too, still with her engagement flowers in her hair. At one point we all hold each other’s elbows and dance around the couple in a circle, laughing and singing at the top of our lungs. I can’t remember the last time I had fun like this, felt joy like this around me.

We stay until the lights go on.

On the way back to the car, Zehra and I lock arms, almost peeing ourselves in a broken English-Turkish discussion about how women don’t fart.

The next morning, when we appear wearily for breakfast, she comes over to me. We put our arms around each other, and squeeze each other again.

This is such a beautiful ode to life and to being human and making change. I love the coffee with salt ritual and the truth it brings.

Also it's true women don't fart! I can attest to it. Xoxoxox

So happy for you Natalie. 13 years! Can’t believe it. All my best in art and life.