The Virgin and the Saint

Halfway through our first date, I excuse myself, find the bathroom (which is, thankfully, in an adjacent building) and close the door.

I lean against the sink, look at my face in the mirror, and take a deep breath.

“Fuck,” I say, quietly.

Then, louder: “FUCK.”

Then: “FUUUUCCKK.”

I mostly swiped right because of the quote he put in his bio.

“All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”

Blaise Pascal. I heard this quote from my first dharma teacher, and it has never fully left my mind.

We texted for days before meeting. In contrast to the, “Hey, how’s your day going?” I get from most guys here, he was endlessly curious about my life. He shared pieces of his story in voice notes sent in stolen moments at his busy job: how he lost everything in the economic collapse in 2019, and how that led him to question everything. We have the same politics; the same collectivist beliefs. We both love nature and dogs and struggle with city life and rage against the system. We both love this land.

He’s named after the patron saint of Lebanon. That’s not giving anything away—it’s one of the most common Christian names here. There’s a mountain named for this saint. You can make a pilgrimage to his grave. He was said to perform miraculous healings.

Now, we’ve been in this restaurant for hours, talking. We’ve gone on rants about religious intolerance, laughed, finished each other’s sentences. We've brought up the same movies, the same books, the same philosophers.

We have the same birthday.

The date is 7 hours long.

The day before Christmas—a few days after the texting began and a couple before we’d actually met—I take a taxi to my dad’s place. The taxi driver is younger than most, energetic and chatty. When I tell him I was born in Canada, he lights up.

“My best friend lives in Canada.” he says. “He tells me that everyone there is so honest! He says that in Canada, they tell the truth 90% of the time. Here in Lebanon, we tell the truth 10% of the time.”

He’s smiling, and his tone is light, but this statement makes my heart turn cold.

“Really?” I say, more quietly than I mean to.

“Just be careful. Especially when it comes to business deals.”

I can’t help myself. “What about… um, dating?”

He laughs again. He tells me he has been married for a long time.

“I only lie to my wife so that she worries about me less,” he says. “But when she finds out I’ve lied, she lies too. See?” he adds, triumphantly. “90%.”

I nod. He catches my eye in the rearview mirror and his smile fades.

“Just be careful,” he says, again.

The texts from the saint slow down, almost imperceptibly. There are fewer good mornings and goodnights, and less voice notes. Or is it just me, interpreting everything through the lens of all my trauma and my baggage? After all, I’m on holidays in my comfortable life while he’s working two jobs and supporting his parents. And he’s still making plans for us: movies we’re going to see, places we’re going to go.

Our second date is three days after the first. We watch a film about revolution (you know the one.) We take turns pausing it so we can leap onto tangents. He tells me he wants to be in a relationship with me.

We go through a bottle of wine, and he asks if there is more.

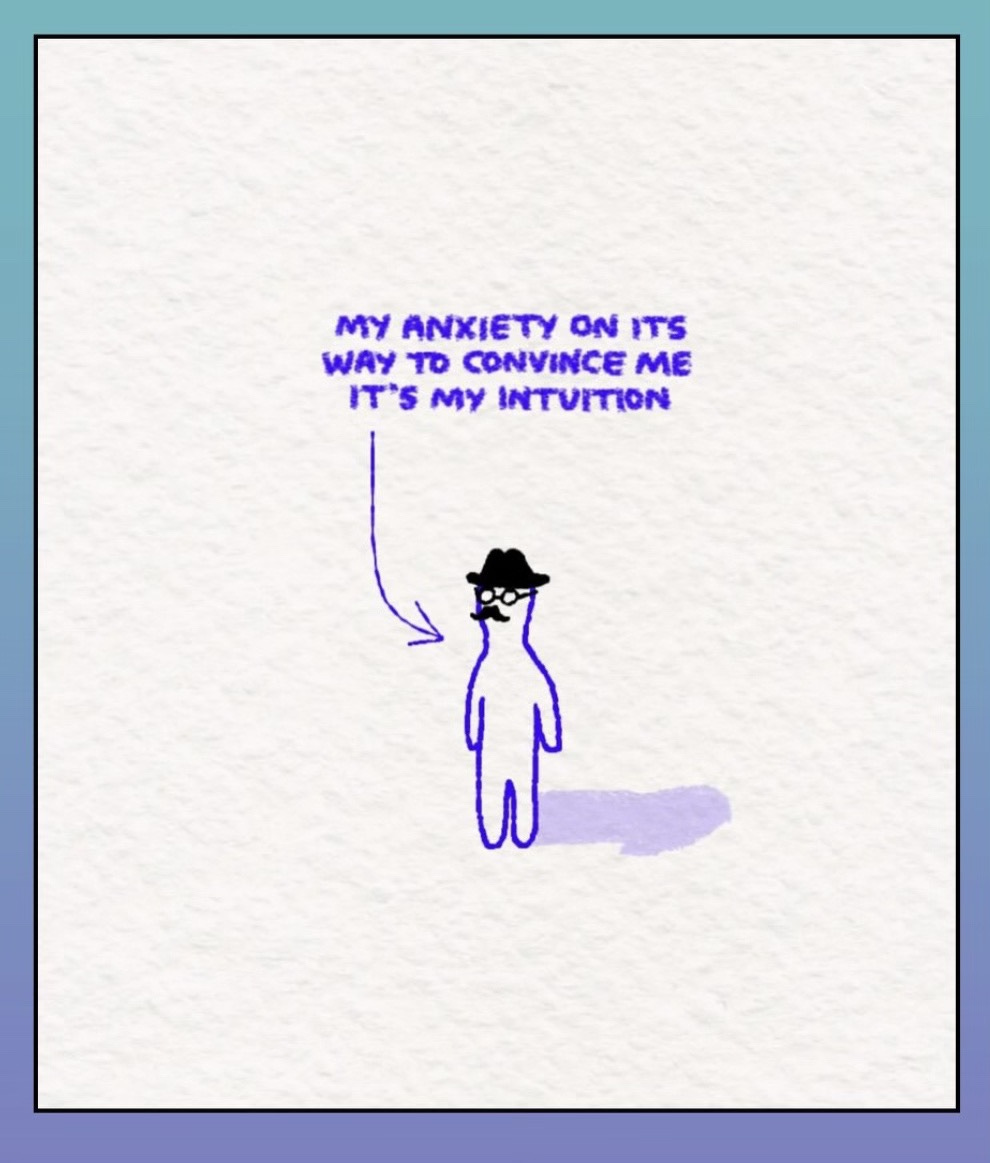

I don’t like how I’m starting to feel, this jitteryness, this butterfly-ey-ness. I’ve lost my appetite. I’m finding it hard to sleep. This shouldn’t be happening—I teach meditation, for fucksakes! I’m coming up on 10 years in recovery.

I meditate extra and do my own kind of prayers, not towards any saints, to help me see clearly.

I talk to my friends, who advise me to be patient. I (ugh) talk to ChatGPT, who assures me that there are no red flags yet. I realize that I’m letting this dude take the lead, and just mirroring him. When I started dating again, I promised myself that I’d never be anything less than fully myself, even if it scared people away. I remembered how the late poet Andrea Gibson said that if you want love, be love.

I send a warm voice note, and immediately receive an even warmer reply, suggesting we see each other that night.

My anxiety calms. I mean, we’re still exchanging messages multiple times a day.

“You need to feel comfortable sharing anything,” he told me, before we even met.

One of my recovery friends tells me, “You can’t learn from mistakes you don’t make.”

The saint lives close to the area where my dad is. The “Christian bubble”, he calls it. He hates the religious divisions in this country.

“Imagine,” he tells me. “Some people here are happy when Israel strikes the south.”

All around the Christian bubble there are images to and shrines of the Virgin Mary. They are in street corners, in parks, in tiny grottos on the side of the road (does it count as a grotto if a person can’t get inside it?) They are in front of apartment buildings, and on the sides of apartment buildings.

I have a soft spot for Mary. Aside from being the only female representation in Christianity, she’s said to be adapted from the Artemis, goddess of wild animals and nature, personification of the moon. Artemis protected young girls. And she was self-wed, which meant she did not need a male deity to be complete. It was the Christians who turned that into a “virgin”. God (literally) knew we couldn’t have a woman walking around who was doing just fine without a dude in her life.

The texts from the saint become shorter and sparser, but he invites me to the mountain village where he’s from. That night, we hang out with some of his friends, who he refers to as “my favourite people to get drunk with”. He says and does some less than stellar things that night, which I write off as cultural differences. The next day, he lights the gas stove, and as it thunders and pelts rain and hail outside, we wrap around each other on the couch watch his favourite documentary, which is also the favourite documentary of one of my best friends in the world. We have dinner at the cosy restaurant of a family he knows. As he drives us back to the city, he holds my hand.

The following morning, he sends me a video a friend of his took us from outside of a rain-spattered window. Someone (him?) has slowed the video down and put it to music. We are sharing a pizza, totally absorbed in each other, hands touching, talking, laughing. Django is nestled in my lap.

I’m speechless.

I respond, asking about a film he wanted to see together.

I hear nothing for two days.

It’s still the holidays, so I spend some more time at my dad’s up in the Christian bubble.

I walk Django around in the sun, communing with the Marys.

How did this happen? I ask them. After all these years and recovery and therapy and goddamn meditation, how is it possible that I fell for this? And why is it making me feel so terrible?

I ask her to hold my shame.

She looks at me, her hands open, her posture of surrender.

Then Django pees at the foot of the statue.

I spend these two days sitting with young girls—the ones I once was. The younger one, still so desperately wanting to be seen and loved; still believing, somewhere in her little heart, that that a man could do that for her. The 16-year old, longing for someone strong and beautiful to fight alongside.

Yes, they assure me: this was a mistake. And one I needed to make it. So I could be reminded that my intuition is never wrong. To remember to protect myself better, especially around men. That intensity does not equal intimacy. And, for the love of god and Artemis and anyone else, to stop lowering my standards—to stop playing small and quiet in order to seem cool and breezy to anyone, regardless of how revolutionary he might appear to be.

Late at night on the third day, he sends me a message.

“Natalie Karneef and Django,” it says, “I miss you.”

My body floods with relief.

Two days isn’t a big deal, right? We hardly knew each other.

“I miss you, too,” I want to say. In other words, “GIVE ME MORE OF YOUR DRUG.”

I think of the young girls. Of Mary. Of the miraculous healing that comes of choosing ourselves.

I turn off my phone and go to bed.

The next day, I respond that it’s good to hear from him, but that I liked him and trusted him, and disappearing like that felt hurtful.

I know that if I send it, I will never hear from him again.

I send it anyway.

Well done! such an old old story, eh? We have been so brainwashed, and so have men. May we all find true refuge (heart emoji, heart emoji, heart emoji, heart emoji)

Brilliant work here. The taxi driver's warning about the 90/10 truth ratio forshadows everything perfectly, yet trusting ourselves after being conditioned to ignore red flags is so damn hard. I've found myselfin similar loops where I knew something was off from day one but rationalized it away becuase I wanted the connection to be real. That final message takes real courage.