This is khachapuri, one of Georgia’s national dishes.

I know.

It’s perhaps not the wisest choice of meals before a day of exploring a city, including two museums, but come on.

I finish as much of it as I can, and walk across one of the bridges into the city centre. The sun is shining. It is, in fact, a stunner of a day.

The museums are all closed tomorrow. I leave Tbilisi the day after that.

When you travel alone, you don’t have to justify your decisions to anyone.

Mtatsminda Park, founded by the Soviets in the 1930s, was once the third most visited public park in the USSR. To get there, you take a funicular that was built in 1905.

I know.

As the doors open and we stream out, I notice that everyone around me is in a couple, or on a family outing.

I make my to the merry-go-round and watch it for a while, telling myself of how poetic this is. I find the roller coaster, and listen to the shrieks of its passengers, trying to absorb some of their joy. I had forgotten this part of traveling alone: how when there’s no one to answer to, all the feelings leap in at once, fighting for attention.

Let’s remember all the people we used to go on roller coaster rides with!

Let’s regret not having kids!

Let’s miss your partner, even thought you specifically came here to be alone!

How often do you get to visit a Soviet era amusement park?

How could you be sad or nostalgic when so many people have it so much worse?

When you travel alone, there is no one to see you sit on a bench in an amusement park and have a little cry.

Feeling lighter, I walk the ferris wheel. I take a car to myself, and soak in the panorama of the city.

And then, since it’s still early afternoon, I head to one of my intended museums.

The Art Palace of Georgia was built by Duke Constantine Petrovich of Oldenburg as a display of affection for his bride, Agrippina Japaridze, who scandalously left her nobleman husband to be with him. (I know!) It’s dripping with chandeliers and wrapped in wallpaper so beautiful I want to eat it. Beneath many of the paintings are detailed stories about not just the artist, but the person being painted. With Zura’s words ringing in my ears, I wonder how many of these people bore witness wars and terrors. How many didn’t live to tell the tale.

One day, we will all become two-dimensional to the living.

I come across a little sign that says “secret room”. I climb a narrow flight of stairs, past some carved stonework, to a bedroom where, as it’s explained, Constantine and Agrippina met in secret.

I wonder how she felt being seen as less than by high society. I hope, maybe a little too fervently, that it was worth it in the end.

Then I go find some falafel.

Many years ago, a group of activists, including one of my meditation teachers, drove Noam Chomsky to the airport. Not surprisingly, they took the opportunity to ask him some questions.

The main one was:

“How do you not burn out?”

Chomsky responded that one of the things that helped him was to see the difference between the ‘profound’ and the ‘important.’ The important, he said—feminism, peace in the Middle East, the struggle against the US military industrial complex—tend to deplete a person’s battery. The profound, on the other hand, is what replenishes us.

Chomsky urged each of the students to engage with not just the important, but also the profound. Art, he said, was a vehicle into the profound. To illuminate the numinous.

When I decided to take this trip, it was with this story in mind.

Or, as adrienne maree brown says,

“Our radical imagination is a tool for decolonization, for reclaiming our right to shape our lived reality.”

There is so much imagination in Tbilisi. There is more beauty in the bathroom of the restaurant I eat at that night than in your average Renaissance painting.

But, as with many of the recommended places I’ve eaten at so far, I also feel like I’m… in the way. The servers seem annoyed. The food is good, but rushed.

It all feels kind of like a show.

And the bill for three falafels would make my Lebanese family’s eyes water.

I’ve never seen more stylish people than the Georgians—everyone, including the grandmothers, put me to shame—so the next day, I go to the shops. But I can’t seem to stay enthusiastic about buying stuff. I walk along the winding streets of Old Tbilisi, peeking into boutiques, stopping at doorways and snaking alleyways. It’s way less fun without Zura and the dogs.

Hungry for some numinousness, I visit a famous church.

I just feel small, and annoyed at the patriarchy.

Obviously, the problem is you.

I haven’t stopped following the news since I got here. In fact, since I’m holiday, I’m reading it that much more. Reading, reposting, signing petitions. It feels like the least I can do for those for whom shopping and art palaces are an impossible dream. I thought this trip would flood me with gratitude. Instead, everything feels like too much, and not enough.

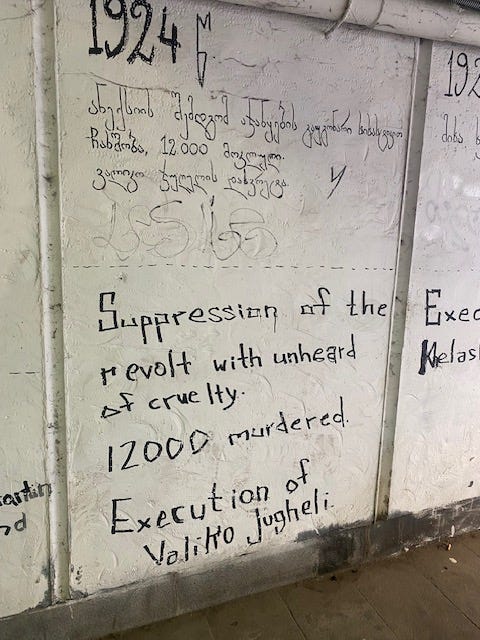

As I walk back to my hotel, the sun is setting, lighting up the city. I pass through a pedestrian tunnel, and see that someone has graffitied hundreds of years of the history of Georgia: invasions, dictatorships, the many attempts to destroy this place and its culture.

12,000 murdered.

Every one of them a life, a thousand stories, a future.

Back in my room, I read a post by a mom in Palestine, She says that when she can—when she has decent internet—she looks at tweets of “normal life”. People having fun, wearing Prada, talking about their interior decorating. She said it makes her happy that people in other places have joy. It gives her hope.

I try to take comfort in this, but it doesn’t really work.

I head to a nearby restaurant that’s said to be favourite with the locals. It’s tucked away beneath a not-at-all-fancy hotel. Georgian folk music is blaring from the speakers, and in the time between ordering and receiving my food, two drunk guys get gently escorted out by two separate cops. The menu includes something called Factory Cheese.

But I feel welcome here.

People are smiling and dancing. The servers joke with each other, taking their time as they carry steaming trays of food across the floor.

I order lobiani, which is a bean stew sprinkled with bacon. And some khinkali—the dumplings Georgia is also famous for—but the waitress tells me I have to order a minimum of 5, which I know will be too many.

“What should I have instead?” I ask.

She gives me a conspiratorial smile. “Bread,” she says.

We both laugh.

She brings me a huge basket of it, warm and fresh.

I head back into into the night with lot more gratitude, and and a tiny bit of joy.

Thank you for describing that feeling of travelling alone so honestly. Travel does crack us open doesn’t it… I suppose it sheds light on the freshly exposed parts of ourselves & let’s out the bits that are no longer needed & thats everything you just expressed in your writing. All those moments … from having a weep at the fairground to laughing with a waitress & everything in between … I always feel like I could be right there with you, thank you for sharing your travels 🙌

This made me happy and sad and pulled me into your world. I love it...thanks Nat.❤️❤️