It’s my first Saturday in Beirut, and I’m late for a meeting.

I speed-walk along, following google map’s directions, dodging honking taxis and scooters racing in both directions, (and sometimes on the sidewalk). I remind myself of my dad’s advice on how to cross the street here: look the driver in the eyes and make sure they see you.

I find myself at a doorway.

Not some kind of beautiful old stone archway, or a French-style wrought iron elevator in one of the neighbourhood’s famous early modern buildings. This doorway goes into a mall. The mall connects two different streets on different levels. I head inside, hopping on the escalator and hoping the google lady’s instructions are right. It’s air-conditioned in here, with elevator music is pumping and people drinking things through straws at chain coffee shops. The walls and floor are glossy black tile. After only three days in Lebanon, it feels wrong.

Since arriving here, I’ve started to get to know the streets in this neighbourhood. On missions to find dog food, buy a SIM card, or stock up on mosquito repellant, I’ve been amazed to see that everywhere is just… shops. Very few chain stores. No one-stop-shopping type places. Instead, there are little corner joints that only sell barber shop products, or household items, or (my favourite) one kind of food. Want fries with your falafel? Better find the fry shop. The person behind the counter will say this while cracking a smile, and even though they’re usually speaking Arabic, you’ll get the gist.

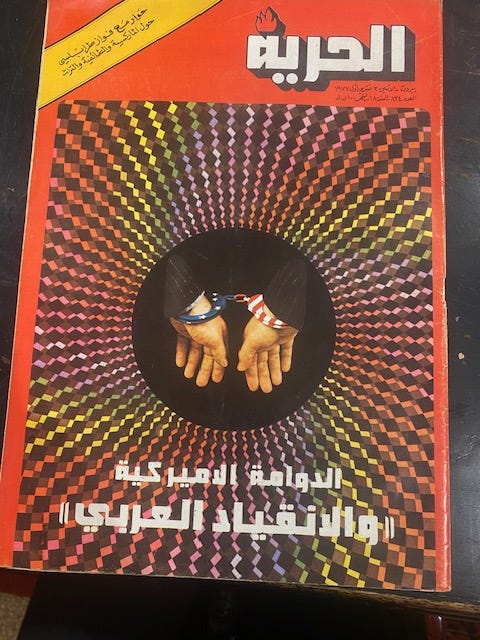

I’m here working on a film based on my dad’s teenager years in this place. I’m lucky enough to be an artist-in-residence at a creative hub, which happens to be next to the park where my grandparents met, and a 5-minute walk from the apartment where my dad grew up.

Somehow, I’ve landed inside the set of my own movie.

I’ve lingered in the doorway of the church where my father was baptized, watching as a lady in a pew murmurs to herself, hunched over a bible.

I’ve stared up at the balcony where my grandmother, who died when I was 4, used to drink coffee on in the mornings.

I think of how few of us get to connect in this way with our past.

One of my aunts, my father’s cousin, invites me and another aunt for a “simple lunch” (hummus, fattoush, sambousek, tiny pickled aubergines stuffed with walnuts, cheese rolls, kibbeh…). I pepper them both with questions about my grandmother and my dad’s uncle, who are both characters in this film. They tell me stories so precious I want to eat them. About the sandwiches my grandma used to make my dad for lunch. How one of them once painted her toenails for her. They interrupt themselves in mid-sentence.

“Have some more humous!”

“Try this, it’s delicious. Guess what’s inside?”

From the balcony of my aunt’s apartment, you can see out to the sea, and to the airport. She points towards the port, where the silos exploded in 2020, and towards south of the city, telling me how the earth shook when the IDF attacked.

We are just down the road from the apartment building where my parents hid out during the civil war.

“Your dad would climb onto the roof at night,” my aunt tells me, filling my plate again, “and take photos of the bombs falling.”

Here are me and Django trying to cross a street. (We spend about a quarter of our days here trying to cross streets.) It’s so loud, and stinky and exhaust-full, and Django is yanking me towards the new smells and putting his life in peril, so I just scoop him up and carry him between cars. On the other side we turn a corner, and I am stopped dead in my tracks. It’s a waft of shisha, or it might be fresh zaatar, or roasting coffee. Suddenly, I’m back in my own childhood, so far away from here, in a place of air-conditioned malls and chain coffee shops, but also a time of going to the “Lebanese store” to buy our tahini and amardeen, and making baked pita bread with majdoul, and waking up to the scent of my dad’s morning stovetop brew.

I recently read “A Woman is a School” by Lebanese writer Celine Samaan. In it, she describes herself as Indigenous to this land.

This stunned me.

I would never have thought of using such a word to describe myself. Of course I am not full Lebanese—technically, by blood, I’m a quarter. But still, among the endless noise and honking and fumes and power cuts; these smells and these memories that are not even mine; I feel more connected in this place than anywhere else I’ve ever set foot.

Back to the meeting I was late for.

I am welcomed, of course, with open arms. There are a handful of us, all women.

At the end, as we’re saying the serenity prayer, the electricity cuts out.

In the pitch black, everyone finishes the prayer and starts hugging each other, as if nothing has happened at all.

If you’d like to make a one-time donation, please click the button below.

I love having a glimpse into your history with Beirut.

I don't really believe in or want to travel anymore but I have always wanted to visit Lebanon, and every time I have plans and start bookings Israel happens. I look forward to reading your updates.